This is the week where people and places publish their list of the best books, “the books most likely to shape life, thought, and culture,” as one list puts it. Despite having no reasonable expectation to be considered, it still bothers me way more than it should to have my books left off the list! Surely it must be an impossible task to make these decisions given the deluge of available content. I feel a bit of this struggle as someone who chooses 15-16 books every year to feature on the In All Things podcast. That podcast averages just under 1000 downloads per month, but I still enjoy curating a reading list of sorts for regular listeners.

Curating reading lists is a serious business. I know I have limited time, energy, and attention for reading and each book represents an expansive imaginative world to explore. So, every year I set out to read 60 books – for class, for research, and for pleasure. Twenty in the spring semester, twenty in the summer, twenty in the fall. During the last few years I’ve become much more intentional in curating my reading list, trying to hit modest goals in terms of women authors, non-majority-culture authors, fiction, poetry, etc. I didn’t quite hit my goals this year, but I came closer. I suppose the point isn’t so much hitting the numbers as sitting down at the table with new voices, allowing my imagination to fire in new ways, growing in curiosity, empathy, and wisdom. But I also want to give myself the freedom to read whatever I’m interested in, to pick up a book and read it “just for the heaven of it.” A serious business, but hopefully not too serious.

In any case, here are the books I read this year.

Fiction, Poetry, and Memoir:

Books I read for the In All Things podcast or to write a review:

Books I read for research, class, or personal interest:

There is some overlap of the books I assign in class and the books displayed above, though I only count the books if I re-read them. Here’s my stack of assigned books (another opportunity to curate a reading list!) for the most recent semester. Yes, I made students read my latest book, which was probably the book that most shaped my life, thought, and culture. =)

This brings me to my top ten. Out of all the books I read, here are my favorite reads this year:

Honorable mentions (Top Ten)

A Burning in My Bones by Winn Collier – the authorized biography of a modern day saint, Eugene Peterson, which made me want to be a saint (in the Peterson sense) as well.

Everything Sad is Untrue by Daniel Nayeri – a book that is difficult to categorize (memoir? young adult lit?) but also difficult to put down. It can be read by middle school students and theology professors with equal enjoyment.

Help My Unbelief by Fleming Rutledge – a book of some of the most magnificent, gospel-saturated sermons, addressed to doubters, I’ve ever read – her Easter sermons in particular brought me to tears.

Low Anthropology by David Zahl – a wonderful book that, with humor and verve, exposes the fantasy self we are all failing to become, and offers gospel hope for healing. (My conversation with the author)

Forgiveness: An Alternative Account by Matthew Ichihashi Potts – as a student of theology and a lover of literature, this was the sort of high level integration that I am jealous of. Potts talks about “writing theology in the margins of literary texts” and that’s a wonderful description of the theological enterprise in general. (My conversation with the author)

My favorite books of the year (Top Five)

5. A Hero Born by Jin Yong/trans. Anna Holmwood (pub. 1957, favorite fantasy book; favorite fun read)

Sometime last year, I ran across someone’s list of the top 50 fantasy books ever. The list-maker was trying to be clever and somehow failed to put Lord of the Rings in the top position. Nevertheless, he made me aware of several books with which I was unfamiliar, including Ken Liu’s The Grace of Kings. But the best thing to come out of that was Jin Yong’s Legends of the Condor series, of which A Hero Born was the first book. I’ve heard it compared to Lord of the Rings (for its epic nature) as well as Pride and Prejudice (for all the screen adaptations, one of which I enjoyed while I rowed on my rowing machine, which also happened less than it should have). In any case, I devoured all four books, but the first one was the best. This was confirmed when I recently recommended it to my 13 year old son – who churns through audiobooks but almost never picks up a physical copy. He is enjoying the book so much that he is reading the physical copy so that he can read it faster. And it does a father’s heart proud to sit next to his son reading books together.

4. The Holy Spirit and Christian Experience by Simeon Zahl (pub. 2020, favorite research book)

Zahl opens with a quote from George Eliot: “Ideas are often poor ghosts; our sun-filled eyes cannot discern them; they pass athwart us in thin vapour, and cannot make themselves felt. But sometimes they are made flesh; they breathe upon us with warm breath…” Zahl is interested in this precise dynamic, how ideas (especially theological ideas, like the good news of Jesus) are made flesh, how they actually change our embodied and emotional experience of the world. Many theological accounts of the Holy Spirit’s transforming work remain abstract and mysterious. But Zahl weaves his way towards an description of the Spirit’s work that prioritizes delight & desire but remains open to mystery, with space for our spiritual mediocrity, when we do not change. A more formal review is forthcoming in the journal Pro Rege next year.

3. Asian Americans and the Spirit of Racial Capitalism by Jonathan Tran (pub. 2022, most challenging book)

This is a book that people have been telling me to read since it came out, and finally I was asked to review it for a journal. It did not disappoint. The first half was a bit of a slog – meticulously researched and incisive in its argumentation. I read 10 pages at a time, taking notes. Then I read the second half of the book in a single afternoon. Tran’s basic argument is that contemporary anti-racism too often reinforces the very divisions it resists. Instead, he points us to an alternative stream of the analysis that sees racism as justification for economic exploitation. This means that Tran’s solution is simultaneously more challenging and more constructive than many anti-racist approaches. It requires us to rethink the shape of our shared life, and to nourish forms of community that testify to the “deep economy” of God. A longer review is forthcoming in the Reformed Journal.

2. The Life We’re Looking For by Andy Crouch (pub. 2022, favorite non-fiction)

For those who will struggle with the academic arguments of Jonathan Tran, Andy Crouch makes a more accessible but similar argument about the shape of our life in a technological world. When I finished reading this book, I said to myself, “that might be the best book I’ve read in five years.” It was a hyperbolic statement, but just barely. Crouch is one of my favorite practitioners of theology and culture. He is a master of the elegant distinction (postures vs. gestures, personalized vs. personal, instruments vs. devices) and the memorable definition (agency = capacity for meaningful action, vulnerability = capacity for meaningful risk, magic = effortless power, the dream of Mammon = abundance without dependence). The book is short and sweet, telling the story of how we became the most powerful people and the loneliest people at the same time, for the same reason. Here’s a review conversation I had with a friend about the book.

1. Piranesi by Susanna Clarke (pub. 2020, favorite fiction)

It’s been a long time since I’ve been so mesmerized by a book. It helps that my original dissertation idea was on Owen Barfield’s ideas about “original participation.” This book allows us to feel what that might be like, while also turning into a thriller along the way. The first 30 pages or so is a bit slow and meditative, and held me with its gorgeous prose. But then the book takes off, and I could not put it down. I have a hard time describing this book and all the ways it tuned my attentiveness to the world, but it gave me a gift of enchantment that is harder to find the older I get.

Bonus: the best page I read this year

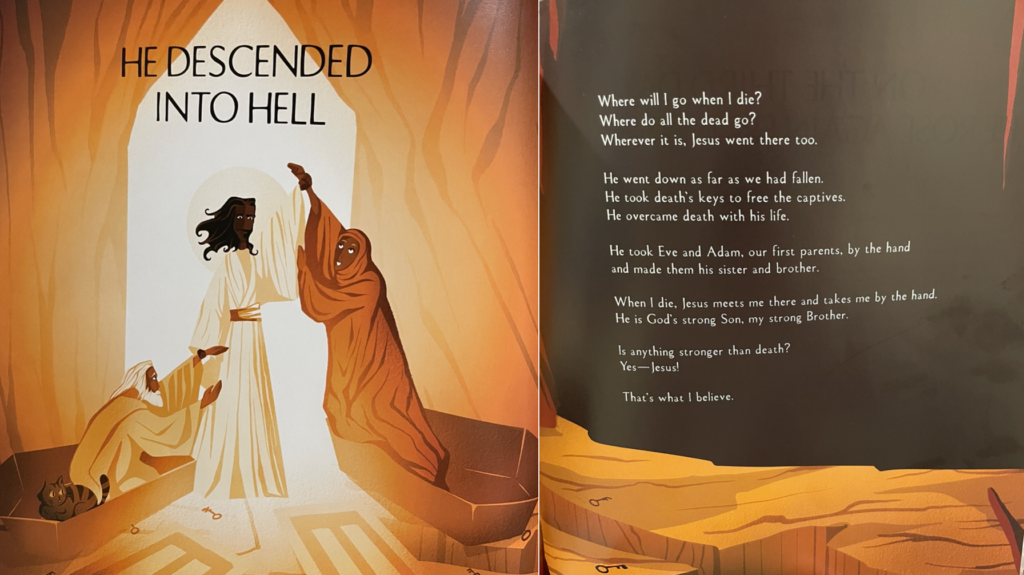

I should also note that although I do not usually read (or count) children’s books, the single best page I read all year came from a children’s book, The Apostles’ Creed for All God’s Children (Ben Myers & Natasha Kennedy). I hope I am not violating any copyright laws to share it here.

“It is a good rule, after reading a new book, never to allow yourself another new one till you have read an old one in between. If that is too much for you, you should at least read one old one to every three new ones. Every age has its own outlook. It is specially good at seeing certain truths and specially liable to make certain mistakes. We all, therefore, need the books that will correct the characteristic mistakes of our own period. And that means the old books.”

–C.S. Lewis, “Introduction” in St. Athanasius, De Incarnatione Verbi Dei (Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1944/1993), 4-5.

Great quote. I’ve never been able to live up to this, unfortunately. Perhaps I should add an “old book” goal for next year.