In pre-modern times, people lived in an “enchanted” world. There was a world of spirits, demons, and moral forces. God acted as the bulwark against evil, the means by which to hold these forces at bay.

This means that the world is intrinsically less manageable, wilder, and more mysterious; I am in a certain sense, at the mercy of the elements. But it also means that the world is intrinsically more meaningful, because my life is found in relation to an enchanted cosmos of which I am a part. I am vitally connected to a world full of powers that can possess me, inspire me, and move through me. This is what Charles Taylor means by the porous self: I am open and vulnerable to the outside world of which I am an intrisic part.

This means that the world is intrinsically less manageable, wilder, and more mysterious; I am in a certain sense, at the mercy of the elements. But it also means that the world is intrinsically more meaningful, because my life is found in relation to an enchanted cosmos of which I am a part. I am vitally connected to a world full of powers that can possess me, inspire me, and move through me. This is what Charles Taylor means by the porous self: I am open and vulnerable to the outside world of which I am an intrisic part.

There are ghosts of this way of experiencing the world in our language (I’m drawing from Owen Barfield here). We still use the word pan-ic but no longer have the sense of Pan acting upon us; we enjoy music but are no longer sensitive to the presence of muses; we feel the wind but no longer feel the breath of a god. In words we catch glimpses of older worlds of meaning. In many parts of the world, this enchanted consciousness continues: the world is alive and filled with spirits, powers, unseen forces. But in the Western world, the enchanted cosmos has been lost, and the porous self has been exchanged with the “buffered self” (detached and disconnected from the world, all the meaning comes from within). How did this happen?

When we talk about this disenchantment, there are really only two options. Either the world was never enchanted in the first place, and that now all of the superstition has been scraped away by science, and so we have begun to live in the world as it truly is. We have, in a sense, emerged from Plato’s cave of ignorance into the sun of scientific certainty.

But the other possibility, the one that Taylor wants us to consider, is not subtraction, but addition. In other words, we have constructed an “immanent frame” that shuts out the transcendent and prevents the possibility of enchantment (though this frame has cracks). This would not be like emerging from a cave but rather descending into one, or building a stone castle and then believing that the cave or the castle, with its stone walls and ceiling, is the only real world.

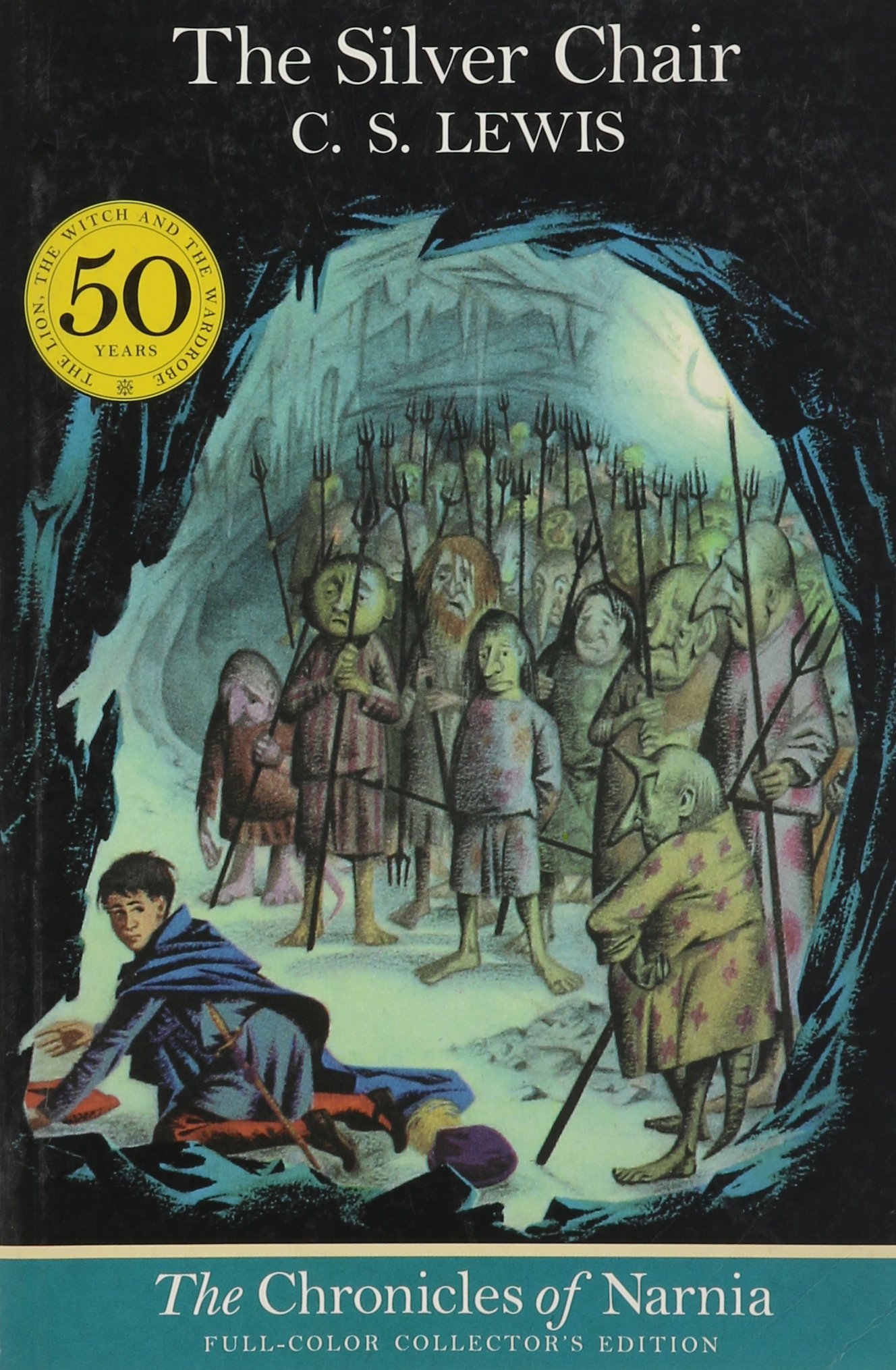

If you’ve ever read C.S. Lewis’ book, the Silver Chair, it puts this in an imaginative form. The heroes Jill and Scrubb descend deep into the earth, into the Underland, where a witch enchants them and begins to convince them that the Overland and everything in it is simply an imaginative projection. They look at a lamp and imagine a much bigger lamp, and call that the sun. They look at a cat and imagine a much bigger and more powerful cat, and call that Aslan. These imaginative projections, the witch tells them, do not truly exist. (If you’ve studied theology, this is the basic idea of Ludwig Feuerbach, who deeply influenced Marx – God is an imaginative projection of our best human qualities).

In any case, in the Silver Chair, here’s how the conversation goes:

Jill: “I suppose that other world must be all a dream.”

“Yes. It is all a dream,” said the Witch.

“Yes, all a dream,” said Jill.

“There never was such a world,” said the Witch.

“No,” said Jill and Scrubb, “never was such a world.”

“There never was any world but mine,” said the Witch.

“There never was any world but yours,” said they.

You see, in the story, “disenchantment” – the stripping away of superstition – is actually an active enchantment that causes the heroes to forget the real world.

Lewis will explicitly use this language in his sermon The Weight of Glory:

“Do you think I am trying to weave a spell? Perhaps I am; but remember your fairy tales. Spells are used for breaking enchantments as well as for inducing them. And you and I have need of the strongest spell that can be found to wake us from the evil enchantment of worldliness which has been laid upon us for nearly a hundred years. Almost our whole education has been directed to silencing this shy, persistent, inner voice; almost all our modem philosophies have been devised to convince us that the good of man is to be found on this earth.”

The parallels aren’t perfect, but I think that this is also what Taylor wants us to consider: that the secular is an accomplishment, a feat of human construction, and ironically a construction from theological materials. Taylor’s work is not an argument for Christianity. It is more of a provocation, an attempt to question the frame that is taken for granted in secular society, an attempt to turn a secular “spin” of reality into a more open secular “take” on reality.

Is it possible that we are in the secular frame, not because superstition has been subtracted, but because an immanent frame has been added, blocking out what is actually there? Why do so many people in the non-Western world still experience reality as enchanted, charged with force and meaning? Is it possible that for all our sophistication we have cut ourselves off from a further form of fullness that goes beyond exclusive humanism?

I certainly don’t want to return to pre-modern times. But the disenchanted world is arbitrary, alienating, and above all, lonely.