I had planned to write this two months ago, when Reimagining Apologetics turned a year old (e.g., one year after its release date). I felt that inner call to write, along with a more-than-ordinary amount of resistance (more on that in a moment). But here it is, a few months late – the story of my first book, for other writers in the thick of things, or for those who are interested in the process and how it feels to release a book into the world.

Chapter One: Doing the research (the dissertation)

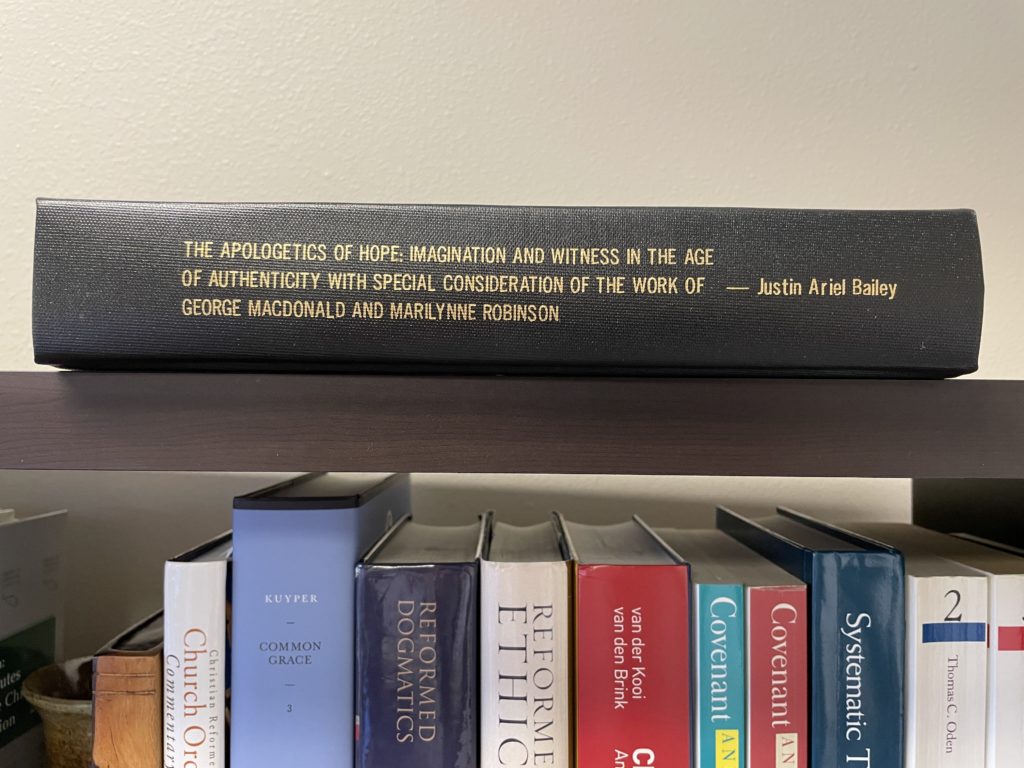

To complete a PhD in theology, you sort of need to write a book, anyway. It is a different sort of book, however, the sort that less than five people will ever read. It is an attempt to make some fresh contribution to the field, written with the insider language of academia, in the unique genre of “doctoral dissertation.” It assumes that its few readers will be well versed in what has already been said on the topic, and yet it also begins with 1-2 chapters of methodological throat-clearing in which the author demonstrates that he/she has digested the secondary literature. Some pages are composed almost entirely of footnotes. But it is a small miracle when it is complete, the result of grit, gracious supervisors, and kind friends who are willing to read it and tell you whether it makes any sense. In any case, the dissertation, which I paid to print, sits on my shelf, and formed the basis of research that was to become Reimagining Apologetics.

Chapter Two: Finding a publisher (the distribution)

At my dissertation defense, my committee recommended that I try to publish my research with a particular academic press. Now, there are different sorts of academic presses. Some will publish your dissertation almost as-is, as a hardcover book that costs $150, printed on demand, to be purchased by a few libraries. But most popular academic presses are interested in sales (to some degree), and so they insist on major revisions. As I heard one acquisitions editor put it: “You have to climb down the mountain of the dissertation and then start climbing up the new mountain of the book.” Although the research is mostly done, it will need to be almost entirely re-written so that it doesn’t feel like a dissertation.

I started by mailing an unsolicited proposal and sample chapter to a person listed on the academic press’s website, only to hear two weeks later that this person was no longer working in this area, and that I should send it to another person by email. Upon reaching that person, he told me (kindly but firmly) that he was not interested in any revised dissertations. The process of learning to write a book proposal, submitting it, and being rejected took about two months.

So, I approached a second academic publisher. The acquisitions editor was enthusiastic and immediately sent it out to external readers. I didn’t hear anything concrete for four months, at which time I received another (very kind) rejection. Although the four external readers recommended the project going forward, the reason for the rejection was this: “you are not yet known.” Later I learned that there was some confusion as to whether I had a permanent academic post (I did), which may have contributed to the rejection.

Although it was a disappointing episode, there was a silver lining. The editor passed along the comments of the external readers, and after receiving permission, their names. It was humbling to hear the caliber of scholars who had taken the time to read and comment on my work. And although they had some criticisms, their substantive engagement was massively encouraging, especially this line: “It is clear that Bailey is a good writer.” I cannot tell you what that line meant to me. It may have been the difference between abandoning the project or pursuing another publisher.

The third try was the charm. My confidence had taken a hit, and so I thought I should try making the case that my book belonged in an academic series on Theology and the Arts. I emailed the editor, and we connected almost immediately. The initial process went much faster; the publishing committee was excited about the project as a standalone, and within a couple months they had approved the book for publication, one year after the dissertation defense.

Chapter Three: (Re)Writing (the drudgery!)

I had already started the slow process of re-writing the manuscript as a fresh book. But having a contract in hand gave me new motivation, and I spent most of the summer writing and re-writing the first three chapters (which were the most dissertation-like). Once the fall semester started, teaching and departmental responsibilities left me unable to give substantive time to the project, and so my editor graciously gave me a two-month extension – to February 2020, which is when I submitted the first draft of Reimagining Apologetics.

Over the next year, as the book made its way through the editorial process, I went through the entire manuscript and rewrote it again, with an emphasis on readability. Along the way, I received comments from my editor and external reviewers, which I did my best to address. I learned that it would be contracted as an audiobook, and so I went through the entire manuscript again, reading it out loud, and ironing out awkward phrases with listeners in mind. When I received the final copyedited manuscript, I was given four weeks to make the corrections, but since I had been working on it throughout the year, it only took two days. I turned in the final manuscript in March 2020, mere days before the world shut down for Covid-19.

Chapter Four: Releasing (the disappointment?)

Reimagining Apologetics was published seven months later, on October 13, 2020. This was 28 months after receiving a contract, 40 months after defending my dissertation.

The publisher sent me a lovely, framed print of the cover and I began receiving media requests for radio and podcast interviews. As I began talking about the book, I realized something: I was incredibly proud of what I had written.

This surprised me, because when I first started the project, my goal was simply to get it published, as a matter of professional course. Part of me hoped it would fly under the radar, because I didn’t want the scrutiny of strangers evaluating my writing. But the longer I worked on it, chipping away, taking the time to choose every word, the more affection I began to feel for the work. The more I wanted it to be noticed, read, and appreciated.

Perhaps the affection resembles the feelings of a proud papa. Authors often compare books to their children, and while that analogy is overblown, there is something right about it. I felt a thrill seeing pictures of my book “in the wild.” I felt ready to contend for it against all reviewers and felt slighted on its behalf when it seemed to be ignored.

And this is the part of this post that I have felt the most resistance to writing. Because I am not sure whether admitting disappointment with the book’s reception is a mark of authenticity or vanity. Maybe it’s both. And yet, there it is: disappointment. Disappointment with the lack of Amazon reviews. Disappointment when formal reviews came out that were cursory or lukewarm. Disappointment with its failure to be noticed by the people and places I wanted to notice.

Perhaps this was to be expected, especially when a book is the physical manifestation of so much time, energy, and attention. To write a book you care about, you must “put your whole self in,” as the song says. My book carries my words, and with them, a piece of my heart. I’m sure the disappointment is partly an extension of my general insecurities, my fear that I am shouting in a hurricane, that I am an insignificant voice, lost in the sound and fury. Deeper still, the fear that the best I have to offer is not good enough.

I’m embarrassed to admit it, like a person shy to share a secret. It feels like an offense – to the mentors who wrote letters of support for the project, the editorial team that took a chance on the project, and all my kind family, friends, and former students who bought a book that they may never finish – to confess that I wanted more.

And yet, amid the feelings of disappointment I can sometimes discern a quieter voice. That voice says things like this: “Maybe it would have never been enough.” “Maybe there are better things than being noticed.” “Maybe you don’t have to keep proving yourself.” “Maybe it’s enough.”

If I can learn to listen to that voice, I feel gratitude. For there have been so many moments where I have been stunned by the excess of care and attention that readers have given my book. I did a two-hour radio interview with a Catholic priest in Pittsburgh who had taken seven pages of notes. I met a retired Methodist minister at a Barnes and Noble who later sent me a moving letter, full of stories from his life that reading my book evoked. I learned that a college of architecture at a Christian university is using Reimagining Apologetics extensively. I recently gave a copy to someone whose work I deeply respect, and he has been sending me progress updates, along with how much he is enjoying it.

Why is it so hard to pay attention to the right things?

Paying attention to the right things doesn’t dissolve all disappointments. But it does situate them. And it offers a different standpoint than disappointment from which to write and work and live.

My hope, as I continue to write, as I look for and take up new projects – is to write from that place. From a place of gratitude rather than disappointment. From a place of abundance rather than scarcity. From a place that is willing to offer up more words – gratuitously – because what has been given is more than enough.

So let me stop and say to anyone still reading: for buying my book, for reading it, for reviewing it, for recommending it to others, for giving it your time and attention, thank you. What a gift it all has been to me.