Graduates of Dordt University, President Hoekstra and members of the board, faculty, staff, parents, alumni, friends, and family:

What a pleasure it is to deliver this commencement address, especially to you the graduates of Dordt University. What a tremendous accomplishment it is to make it to this day, the end of this part of your journey, one filled with moments and milestones, with tears and great laughter.[i]

And yet our current crisis threatens to swallow all sense of scale, and to leave us at the end with a bitter taste in our mouths. We have done our best to honor your great achievements on this day. But how we wish you were here in person, crammed together on this stage with beloved classmates, waiting for your name to be called, and for your loved ones to cheer. We still celebrate you as emphatically as we can. But this, my friends, is not the way it’s supposed to be.

In the face of all the sickness and suffering, it can feel wrong to name our smaller griefs: the loss of capstone experiences that cannot be replicated online, senior seasons cut short, the sudden realization that a chapter has ended without offering you the usual rites of closure. The absence of friends close at hand as you – armed with coffee and memes – confronted your final week of finals. The release of taking that last exam and physically walking out of the classroom for the last time. It is fitting to grieve these quieter losses, these smaller defeats, even if we refuse to be defined by them.

But perhaps the opportunity to *begin* the next chapter of your life in the midst of the coronavirus will prove to be an unexpected gift. For here are a few final lessons that you cannot ignore. You are irreducibly interdependent. Control is an illusion. One day, you will die. These simple, obvious truths may not be pleasant lessons to learn. But here is wisdom: the wisdom of weakness.

And perhaps it is also the case that you are being sent out for just “such a time as this.”[ii] For there are many in our world who know how to glory in strength, but much fewer who know how to rejoice in weakness. In a world that has been obsessed with becoming bigger, faster, and stronger, we suddenly have been forced to become smaller, slower, and weaker. And we need servant leaders in all spheres of society who know how to travel light, how to move at a sustainable pace, and how to operate with a different understanding of power. We need strength that has been made perfect in weakness.[iii]

You, the graduates of Dordt university, are invited to answer this call. You see, at the very heart of the Christian faith, and at the very center of our university crest, is a symbol not of strength, but of weakness. It is not a crown (which I remind you is corona in Latin), but a Cross. This Cross reminds us how God heals his beloved creation: not through the world’s power and glory, but through the Messiah’s weakness and humility.

What does it mean to place such a symbol – the Cross – at the center of a University, at the center of our vocations, and at the center of our lives as we face this brave new world together?

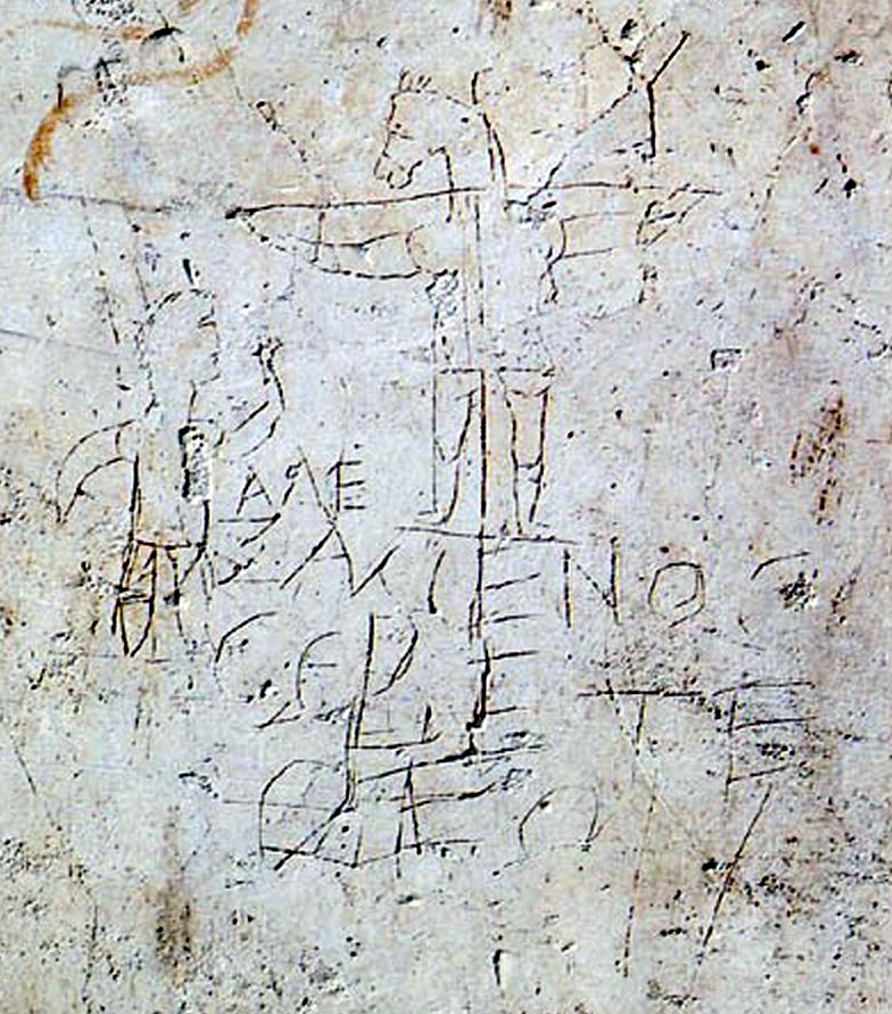

The Cross, of course, is arguably the most recognizable symbol in the world. It is dear to us, but it is also familiar to us. And that means that we can become inoculated to its brutality and to its beauty. Recall that for the first three hundred years of Christian history, the Cross was *not* a symbol of Christianity. It was instead a symbol of imperial cruelty, a technology of dehumanization, a degrading public spectacle intended to humiliate the nobodies it killed. The earliest depiction of Jesus on the Cross is found in a piece of graffiti art, where Jesus is given the head of a donkey. It is the work of one slave mocking another for worshipping such a silly god.[iv] Fleming Rutledge reminds us: “until the gospel of Jesus Christ burst upon the Mediterranean world, no one in the history of human imagination had conceived of such a thing as the worship of a crucified man.”[v]

Why, on this day of celebration, do I remind you of the brutality of the Cross? It is because before the Cross was transfigured into a sign of divine love, it was first a symbol of human evil. The Cross forces us to come to terms with the ugliness and barbarity of the world, and our part in it. It forces us to come to terms with how severely we fail to live up to our highest ideals. The best and the brightest religious and political minds conspired together to kill Jesus. The best and the brightest minds devised the tower of Babel and the violence of Babylon.[vi] The best and the brightest minds, again and again, turn their creativity towards idolatry and injustice. As they say in Alcoholics Anonymous: “Our best thinking led us *here*.”

Every member of faculty has specific faces in mind when I say on their behalf that you are some of the best and the brightest students we been privileged to teach. But if you – and your education – are never humbled by the Cross, then you will be surprised by failure and futility, when things break down and shut down and when the best and brightest let you down. If you fail to be humbled by your capacity for evil, by your complicity in injustice, by the darkness that is not just “out there,” but also “in here,” you will have nothing to say when things fall apart. And so, you will be unable to grasp the deep hope that only the Cross can provide.

For once the Cross has humbled us, it offers hope, perhaps at the moment we least expect it and least deserve it. Indeed, because of Jesus, this symbol of the worst that humans can do has been transfigured into a sign of the best that God can do.[vii] For what looked like the ugliest thing humans could imagine has somehow become the most beautiful: God “taking upon himself the curse that lay on us,”[viii] shaming principalities and powers,[ix] and offering an example “that we should follow in his steps.”[x] And so, we place the Cross in the center of our university crest, in the center of our worship, and even in the center of our tombstones. We do so in hope that what happened at the Cross will make all the difference for us, body and soul, in life and in death.[xi]

Like shattered pottery, repaired with golden glue, the Cross repairs our brokenness with grace, opening up the possibility of redemption: that God can restore the years that the locust has eaten,[xii] that sad things may come untrue.[xiii] For the Cross, when seen in light of the resurrection tells us that even death will be swallowed up in the end.[xiv]

And so, we no longer think of the Cross as an instrument of brutality. We no longer associate it with shame and degradation. For us it is an image of hope, love, and life, and with good reason: death is defeated, and he is risen. But if we are not careful, we can forget the weakness, humility, and self-giving that the Cross places at the very heart of Christianity, and at the very center of our vocation.

I find it intriguing that when Christians made art in the catacombs, during that first three hundred years, they avoided depicting Jesus’ crucifixion directly. But what you find instead is something much more profound. One of the most frequent images found in those dark places is a figure of a person praying. And how are they praying? Arms outstretched, in the shape of the cross. Scholars say that this prayer posture distinguished early Christians from pagan worshippers who tended to raise their hands in the air.[xv] When Christians prayed, they stood cruciform, in the shape of the Cross. It is like they were saying, my life is my prayer, my life is my offering; it shows my Lord, the humble king who was crucified for me. This is how I will live, and this is how I will die.

When I imagine these Christians praying and painting beautiful things in dark places, I feel a swell of pride. These are *my* people. And I hear the call to continue in their footsteps, following the Crucified Lord in broken joy. I commend this posture to you as you start this chapter amidst a global pandemic.

As Jesus stretches out his arms, he shows us a whole new shape of life: not grasping because we feel empty but giving because we are full.[xvi] Because of the Cross, our lives are anchored, hidden with Christ in God.[xvii] That means we are able to grieve, but also to let go. It means the ability to sit long in a season of disappointment and yet not to be defined by it. It means the hospitality to make space for others as they struggle and mourn, wrestle and wait. It means seeking to bless rather than curse, seeking to leverage all we have learned in service. It means that servanthood is our identity, not our strategy.[xviii]

To let the Cross set our posture means to open our hands and our hearts to embrace wholeheartedly whatever God entrusts to us. In a time when we are tempted to close in on ourselves, to scramble for control, may we open up in this cruciform posture, looking for ways to give, serve, and to be present amidst loss, grief, and weakness. We like to talk about transformation here at Dordt, and with good reason. But the Cross calls us to remember that there are things that only God can transfigure.

At the very end of the Hobbit, after Bilbo’s tremendous feats of bravery, Gandalf says to him: “You don’t really suppose, do you, that all of your adventures and escapes were managed by mere luck, just for your sole benefit? You are a very fine person, Mr. Baggins, and I am very fond of you, but you are only quite a little fellow in the wide world after all.” Bilbo’s response is to laugh and to say, “Thank goodness!”[xix] And we can say thank goodness with him, rejoicing in our smallness. Because we know that while we are called to play our part with all our might, the world does not rise and fall on our effort alone. We are called to use every drop of our strength to do as much as we can do. But then in humility, we step out of the way. For the Cross reminds us that after we have done all we can, God may have another move.

Graduates of the class of 2020, this is the wisdom of weakness. Our education in this sort of wisdom has just begun. But there is no better place to learn than the foot of the Cross. So may you go forth in broken joy, praying and painting beautiful things in dark places. And may God establish the work of your hands.[xx]

[i] “Tears and great laughter” is the phrase Frederick Buechner used to narrate his own conversion. Frederick Buechner, The Alphabet of Grace (San Francisco: Harper Collins, 1970), 114.

[ii] Esther 4:14

[iii] 2 Corinthians 12:9

[iv] See the discussion in Richard Viladesau, The Beauty of the Cross: The Passion of Christ in Theology and the Arts, from the Catacombs to the Eve of the Renaissance (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006), 19-20.

[v] Fleming Rutledge, The Crucifixion (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2015), 1.

[vi] Genesis 11, Revelation 18

[vii] This turn of phrase is from Malcolm Guite: “In a daring and beautiful creative reversal, God takes the worst we can do to him and turns it into the very best he can do for us.” Malcolm Guite, The Word in the Wilderness (London: Canterbury Press, 2014), 8.

[viii] Heidelberg Catechism Q39.

[ix] Colossians 2:15

[x] 1 Peter 2:21

[xi] Heidelberg Catechism Q1

[xii] Joel 2:25

[xiii] J.R.R. Tolkien, The Return of the King (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1965), 230

[xiv] Isaiah 25:8; 1 Corinthians 15:54

[xv] Viladesau, The Beauty of the Cross, 42.

[xvi] Philippians 2:1-8

[xvii] Colossians 3:1

[xviii] I learned this lovely phrase from Crawford Lorritts.

[xix] J.R.R. Tolkien, The Hobbit (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2013), 374

[xx] Psalm 90:17